Throughout history, the exploitation of hype around a newfound technology is very well known. A century ago, people sold mineral oil dubbed as snake oil as a panacea for all cures. Though that myth has been busted, these snake-oil merchants took different forms over the years. Today, they seem to have entered the realms of AI and other advanced fields.

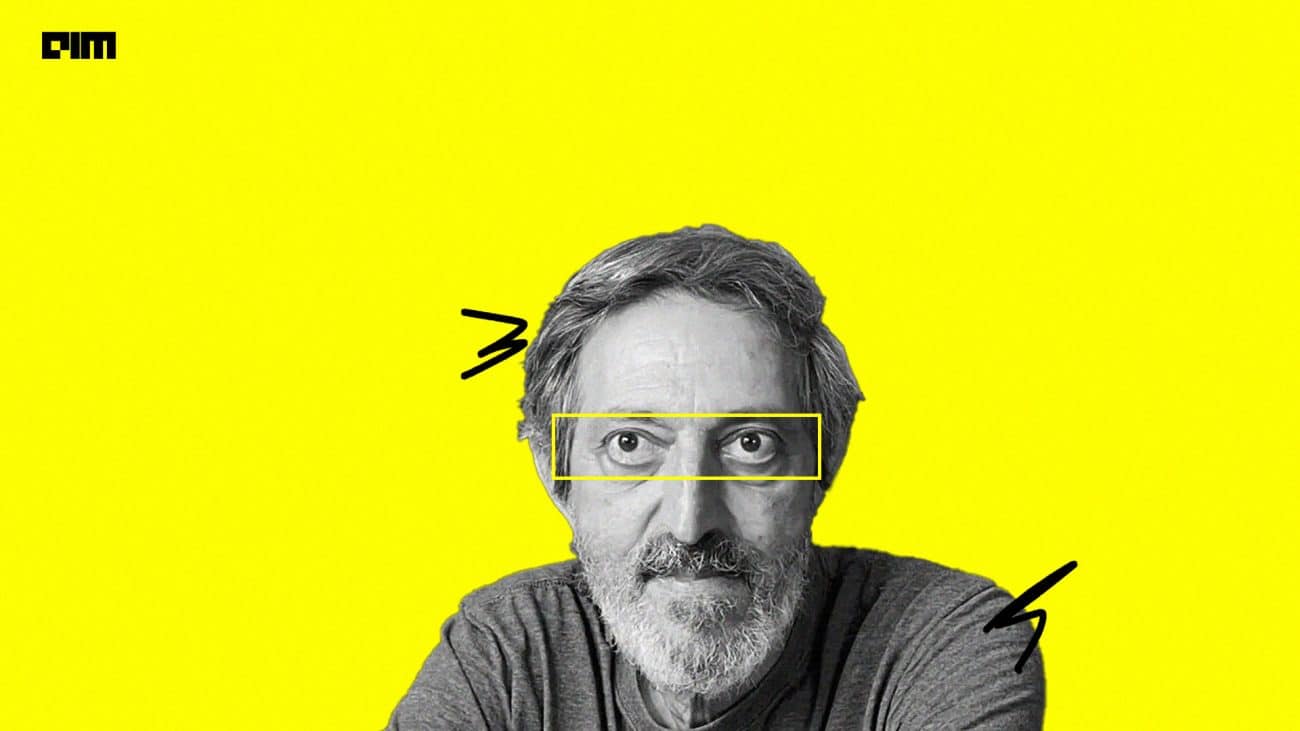

Addressing the recent hype and the emergence of snake oil salesmen in AI, noted Princeton professor Arvind Narayanan, who is well-versed with ethics in artificial intelligence, did some machine learning myth-busting at a talk he gave recently at MIT. His talk was titled, “How to recognise AI snake oil”.

A noted Princeton professor who is well-versed with ethics surrounding artificial intelligence, did some machine learning myth-busting at a talk he gave recently at MIT.

In his talk, Professor Narayanan, who is an is an Associate Professor of Computer Science at Princeton at Princeton University, spoke in detail about how companies have started riding high on the AI hype train.

He spoke about:

- How AI excels at some tasks, but can’t predict social outcomes

- How we must resist the enormous commercial interests that aim to obfuscate this fact

- And how, in most cases, manual scoring rules are just as accurate, far more transparent, and worth considering

Applications of AI range from suggesting which book to buy on Amazon, to deciding if a candidate is fit for the job.

In the former case, a bad book recommendation would spoil a day or two of fun, but a bad rejection can derail an individual’s career forever.

We seem to have decided to suspend common sense when ‘AI’ is involved

The results from ML-based decision in tasks such as prediction of criminal risk and job hires imply that they edge the conventional methods — but not by much. Even linear regression with few features is considered to be doing fine.

So, what’s to be done about this? The first thing would be to be aware of the implications of inappropriate usage of AI.

Identifying Fashionable Nonsense

In his presentation, Professor Narayanan described how companies are using AI to hire candidates based on just a 30-second video. They dish out a blueprint with scores based on different aspects such as speech patterns that have been grasped from that video. These scores are then used to decide whether that candidate is a suitable hire or not.

The Princeton professor warns of the rise of bogus AI as these hire-with-AI companies are being funded with millions and are doing aggressive campaigning to bag clients who are “too cool” to put humans in the hiring loop.

The main reason these companies get away with such ridiculous-sounding AI applications is because of the reputation that AI gets from other quarters.

Key point #3: transparent, manual scoring rules for risk prediction can be a good thing! Traffic violators get points on their licenses and those who accumulate too many points are deemed too risky to drive. In contrast, using “AI” to suspend people’s licenses would be dystopian. pic.twitter.com/05gJHwckZi

— Arvind Narayanan (@random_walker) November 19, 2019

Research from the likes of DeepMind announce successes like AlphaGo. Whenever this happens, there is a positive buzz created in the community. So, a few companies like to be associated with AI just to tap into some of this optimism.

From the marketing perspective, this does sound great but those at the receiving end of naive AI applications are only left with bitter after tastes.

AI for medical diagnosis or even detecting spam on email is fine because given enough data, a machine learning model can improve and be made reliable. However, in the case of ethical, social dilemmas such as public policing or criminal prediction, anomalies emerge and can prove fatal.

Princeton’s Narayanan lists the following use cases where the potential for pushing “snake oil” merchandise:

- Predicting criminal recidivism

- Predicting job performance

- Predictive policing

- Predicting terrorist risk

- Predicting at-risk kids

In the above cases, which are fundamentally dubious, as the professor likes to call them, the ethical concerns will be amplified with inaccuracies in model output.

The Need To Track Down Bogus AI, Going Forward

We have heard news where people were turned away at the border because some algorithm skimmed through their social media and categorised them as terrorists. China uses public data to give credit scores to individuals and then there is facial recognition deployed at a school.

The beginnings of such implementations, though reek of benevolence, have the potential to be misused. They should scare the policymakers enough before generalising them on a large scale.

The lack of explainability in AI-based solutions has been a tough nut to crack for the researchers. Though there is active research in this domain to make AI more explainable, right now putting social dilemmas at the helm of algorithms might prove disastrous.

Though this talk has scepticism lingering around it, this is more AI-aware than anti-AI. The speaker is in no doubt of the rich potential of this new technology. He only warns us of it being used as a naive substitute for common sense.

With governments incorporating AI into their yearly plans, city planning and many other decisive tasks, a healthy dose of scepticism is necessary.