The Turing Test is one of the few things that comes to our mind when we hear about reasoning and consciousness in artificial intelligence. But apart from the Turing Test, there is one more thought process which shook the world of cognitive sciences not so long ago. Four decades ago, John Searle, an American philosopher, presented the Chinese problem, directed at the AI researchers.

The Chinese Room conundrum argues that a computer cannot have a mind of its own and attaining consciousness is an impossible task for these machines. They can be programmed to mimic the activities of a conscious human being but they can’t have an understanding of what they are simulating on their own.

“A human mind has meaningful thoughts, feelings, and mental contents generally. Formal symbols by themselves can never be enough for mental contents, because the symbols, by definition, have no meaning,” said Searle when questioned about his argument.

What Is The Chinese Room Conundrum?

Searle explained the concept eloquently by drawing an analogy using Mandarin. The definition hinges on the thin line between actually having a mind and simulating a mind.

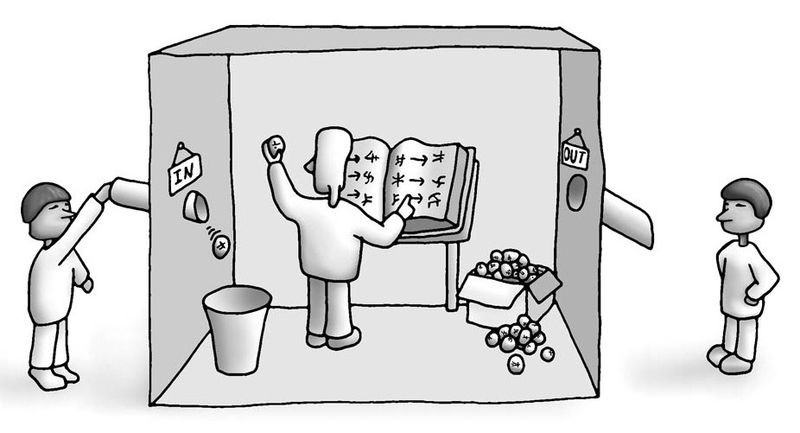

Searle’s thought experiment goes like this:

Suppose a closed room has a non-Chinese speaker with a list of Mandarin characters and an instruction book. This book explains in detail the rules according to which the strings (sequences) of characters may be formed — but without giving the meaning of the characters.

Suppose now that we pass to this man through a hole in the wall a sequence of Mandarin characters which he is to complete by following the rules he has learned. We may call the sequence passed to him from the outside a “question” and the completion an “answer.”

Now, this non-Chinese speaker masters this sequencing game so much that even a native Chinese person will not be able to spot any difference in the answers given by this man in an enclosed room.

But the fact remains that not only is he not Chinese, but he does not even understand Chinese, far less think in it.

Now, the argument goes on, a machine, even a Turing machine, is just like this man, in that it does nothing more than follow the rules given in an instruction book (the program). It does not understand the meaning of the questions given to it nor its own answers, and thus cannot be said to be thinking.

Making a case for Searle, if we accept that a book has no mind of its own, we cannot then endow a computer with intelligence and remain consistent.

The Following Questions

How can one verify that this man in the room is thinking in English and not in Chinese? Searle’s experiment builds on the assumption that this fictitious man indeed thinks in English and then uses the extra information from the hole in the wall and masters those Chinese sequences.

But Turing’s idea was that no such assumptions should be made and that comprehension or intelligence should be judged in an objective manner.

The whole point of Searle’s experiment is to make a non-Chinese man simulate a native Chinese speaker in such a way that there wouldn’t be any distinction between these two individuals.

If we ask the computer in our language if it understands us, it will say that it does, since it is imitating a clever student. This corresponds to talking to the man in the closed room in Chinese, and we cannot communicate with a computer in a way that would correspond to our talking to the man in English.

The texts or the set of instructions cannot be dissociated from the man in the experiment because this instruction, in turn, is prepared by some native Chinese person. So, when the Chinese expert on the other end of the room is verifying the answers, he actually is communicating with another mind which thinks in Chinese. So, when a computer responds to some tricky questions by a human, it can be concluded, in accordance with Searle, that we are communicating with the programmer, the person who gave the computer, a certain set of instructions to perform.

Outlook

Any theory that says minds are computer programs, is best understood as perhaps the last gasp of the dualist tradition that attempts to deny the biological character of mental phenomena. Searle’s speculation in spite of its inadequacies tests the boundaries of AI and makes an attempt to dispel the weak ideas of pseudo-intellectual futurists. Searle in negating the capabilities of AI, has, in fact, exposed the blind spots in our pursuit of General AI and made it more robust.