Have you heard about Rudolf Arnheim? Well! Rudolf was born in Germany in 1904 and was an art and film theorist. In 1968, he was invited to join Harvard University as a Professor of the Psychology of Art. His works, such as “Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye” (1954) and “Visual Thinking” (1969), investigated art through the lens of science and sensory perception.

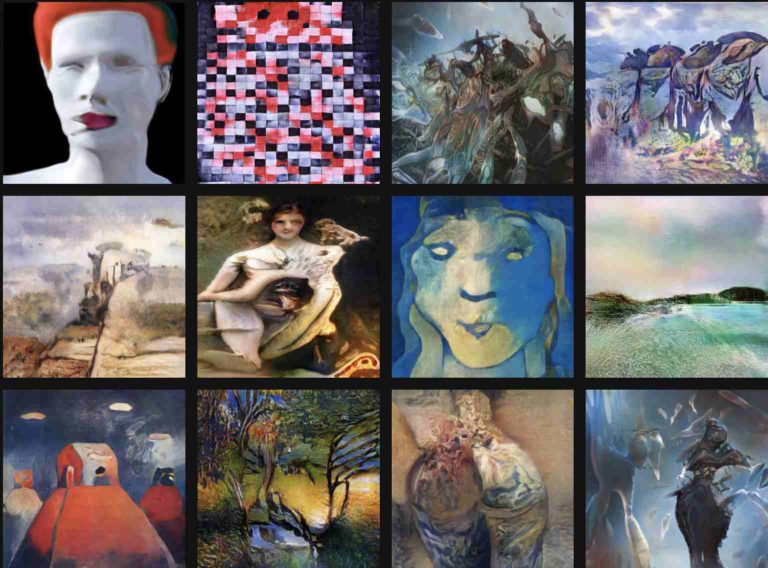

As DeepMind explains in its blog, “Our computational creativity work uses computers as tools for generating visual ‘art’ in a way that is inspired by Arnheim’s formalism.” The research lab took to Twitter to introduce Arnheim – a generative algorithm for producing pictures made with grammatical brushstrokes.

Arnheim – a generative algorithm for producing pictures made with grammatical brushstrokes.

— DeepMind (@DeepMind) November 10, 2021

Interested in trying it out? Type in the title of the picture you want and play around with the code to modify how brushstrokes are generated: https://t.co/iz7C86CQbs 1/ pic.twitter.com/KcrbTZyECB

To that end, DeepMind offers two Colabs for people to easily invent their own generative architectures and paintings, which includes:

- Arnheim 1: The original algorithm from the paper Generative Art Using Neural Visual Grammars and Dual Encoders running on 1 GPU allows optimization of any image using a genetic algorithm. This is much more general but much slower than using Arnheim 2, which uses gradients.

- Arnheim 2: A reimplementation of the Arnheim 1 generative architecture in the CLIPDraw framework allowing optimization of its parameters using gradients; much more efficient than Arnheim 1 above but requires differentiating through the image itself.

For those who want to play around with the code to modify how brushstrokes are generated, one can get here.

These two Colabs are examples of how AI can be used to augment human creativity by suggesting possible ways of forming a depiction.

Alva Noë defines art as the process of reorganization of experience, effectively as a kind of visual philosophy. Whilst we are still very far from an algorithmic understanding of this deeply human process, the colabs here show that to some extent, one minor aspect can be understood by synthesis, namely, how decisions are made about which ordered marks to make to produce a depiction efficiently. The team hopes that others will modify these algorithms in fascinating ways.